Decoding Working Capital: An Overlooked Factor in M&A Transactions:

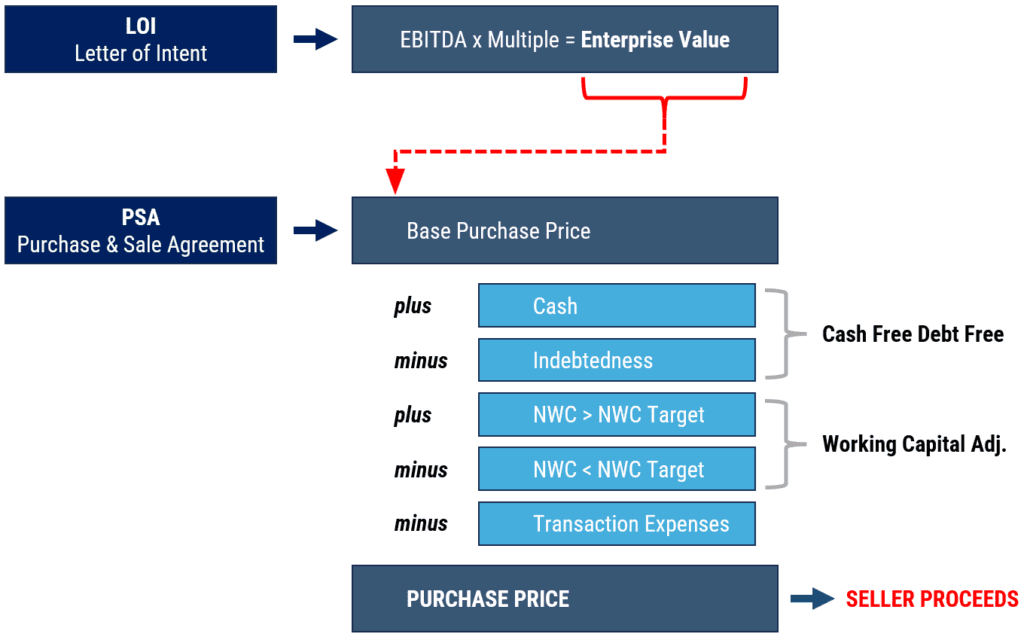

When selling a business, the price that a buyer is willing to pay includes all of the assets and certain liabilities of the company, including machinery and equipment, customer and supplier contracts, lease agreements, and goodwill. The purchase price also includes a certain level of working capital required to operate the business. This is why working capital analysis is a key value component and piece of financial due diligence when selling a business. Business owners typically keep a close eye on working capital during normal operations, and during a sale process, it is no less important to monitor trends to avoid unwanted adjustments to the purchase price. In this article, we will discuss how to analyze historical working capital and considerations for M&A transactions.

What is Working Capital:

Working capital in an M&A transaction is generally defined as current assets (excluding cash that the Seller keep in a “cash free – debt free” transaction) minus current liabilities. From the perspective of the business owner or Seller, it is often referred to as “the cash tied up in the business”. The purpose of tracking working capital is to understand the ongoing capital (cash/credit) requirements of a business. The breakdown of working capital is described below:

Current Assets (accounts that can be converted to cash within the next 12 months)

– Accounts receivable

– Inventory, including raw materials, finished goods, and work in process

– Prepaid expenses

Current Liabilities (accounts to be paid within the next 12 months)

– Accounts payable

– Accrued liabilities, such as insurance, employee wages and bonuses, and paid time off may be negotiated into working capital depending on the situation

Excluded Accounts

– Cash (Seller keeps the cash on their balance sheet at close other than customer deposits)

– Debt (Seller is liable for short-term and long-term debt at close, usually paid off with proceeds of the sale)

Working Capital Considerations by Industry:

Working capital accounts vary from business to business depending on the operating structure. The three examples below demonstrate how the differences in business models/operating structures impact working capital intensity:

Example 1: Software business, $10M revenue (low working capital intensity)

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities |

Total Current Assets = $2,160,000 |

Total Current Liabilities = $2,460,000 |

Working capital = -$300,000

Software businesses can deliver negative working capital because they do not generate inventory and carry deferred revenue balance from offering subscriptions to its customers.

Example 2: Consumer products business, $10M revenue (“normal” working capital intensity)

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities |

Total Current Assets = $2,350,000 |

Total Current Liabilities = $1,750,000 |

Working capital = $600,000

Consumer products businesses generate a larger amount of working capital compared to the software business. They generate higher inventory and accounts payable balances. A “healthy” consumer products business should generate on average a non-cash working capital balance that is 8.5% of sales.

Example 3: Construction business, $10M revenue (high working capital intensity)

| Current Assets | Current Liabilities |

Total Current Assets = $3,200,000 |

Total Current Liabilities = $1,600,000 |

Working capital = $1,600,000

Construction businesses generate high working capital with long project times resulting in greater accounts receivable, and strong seasonality in some regions, as the work is performed during the summer months.

Working Capital Considerations in M&A:

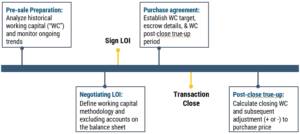

During the sale process, there are four key events that involve working capital: pre-sale preparation, the letter of intent (“LOI”), the purchase agreement, and the post-close true-up.

Working Capital Timeline

Pre-Sale Preparation:

At the onset of the sale process, Chinook recommends business owners engage an accounting firm to perform a sell-side Quality of Earnings report (“QofE”). Refer to our previous article: It’s about trust: why you should invest in a Quality of Earnings Report. As part of the report, the accounting firm will calculate adjusted working capital and model historical working capital trends, net of any accounts that would be excluded from a sale. This provides investors with an initial understanding of working capital requirements before signing a Letter of Intent.

Analyzing historical working capital is important to discover any seasonality. Beyond the historical analysis, it is important to monitor ongoing working capital on a monthly basis to identify any changes to historical trends.

Letter of Intent (“LOI”):

In a typical letter of intent, investors will provide an intention for how working capital will be treated in a transaction. Refer to our previous article: Some Say LOI’s Aren’t Worth the Paper They’re Printed On. We Disagree. Clearly defining working capital in an LOI is important because it reduces disagreements during the closing process. In addition, the QoE report provides a clear definition of working capital. The methodology differs depending on the specific current asset and liability accounts relevant to the business.

A fair definition of working capital ensures both the Seller and Buyer are treated equally – if the Seller overdelivers or underdelivers working capital at close compared to historical averages, the Buyer should either compensate the Seller or be compensated.

Purchase Agreement:

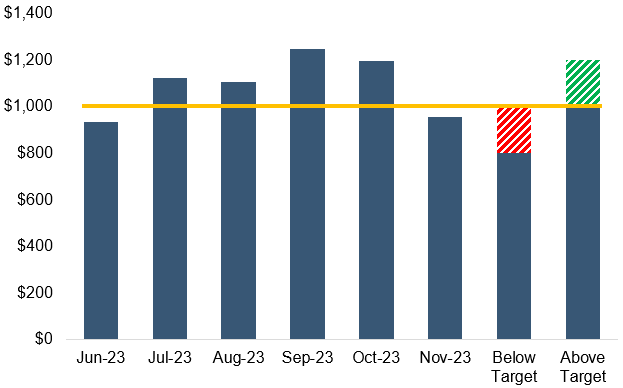

In the Purchase Agreement, working capital components are further negotiated and defined. This includes establishing a Target, a potential holdback amount, and a True-Up Period post-close. The working capital Target is an average historical working capital level to ensure a fair level is delivered at close. The working capital Target is typically based on an average level over the previous 12 months to account for any seasonality or month-to-month fluctuations in demand or output. The transaction may also include a working capital escrow, which is an amount of money set aside in an escrow account to secure the Seller’s obligation to meet any working capital shortfalls after closing. The working capital Target may also include a collar, which is a range above and below the working capital Target within which no adjustment is made if the final WC amount falls within this band.

Post-close True-up:

A post-close true-up is necessary because the closing date balance sheet will not be finalized until about 60-90 days after closing. To illustrate the post-close true-up, the graph on the right presents two scenarios where closing working capital is either above or below the established Target amount. Assume the Target is $1M, the Seller delivers $800k of working capital at Close. As such, there would be a $200k dollar-for-dollar reduction of the purchase price. If a holdback was in place, the adjustment would come out of the escrow. If there was a collar, this could result in a little to no adjustment. This could occur from unexpected operational issues resulting in increased expenses and therefore accounts payable, lower than expected inventory levels, or lower levels of accounts receivable than estimated.

In the “Above Target” scenario, the Seller delivers $1.2M of working capital at Close. As such, the Seller is owed $200k from the Buyer. This could occur due to stronger-than-expected business performance resulting in increases in accounts receivable, inventory, or a decrease in accounts payable right before closing.

The post-close true-up mechanism, as defined in the Purchase Agreement, ensures that the Buyer receives enough working capital to meet the ongoing needs of the business, while the Seller is appropriately compensated for the working capital delivered.

Critical Metric:

Working capital is a critical metric for any company and plays an important role in the M&A process. Understanding historical working capital trends and knowing how to negotiate the working capital components in a transaction can result in a smoother transaction and more value to the Seller.